As much as I want to believe in the purity of our local town and people - there is no error on these records. While today the “South” is the featured bad guy in slavery and civil rights history, the truth is that right here in Somerset County the sin of slavery once existed.

What hypocrisy it would be to establish a country based on freedom and democracy, yet deny freedom to blacks in that same country. That mentality slowly took root in the Northern States of the U.S. By 1800 most Northern States had passed laws that would gradually free those enslaved. But New Jersey had been so badly damaged and looted in the war that the freeing of the slaves was judged to be too much of an additional economic burden that it was delayed.

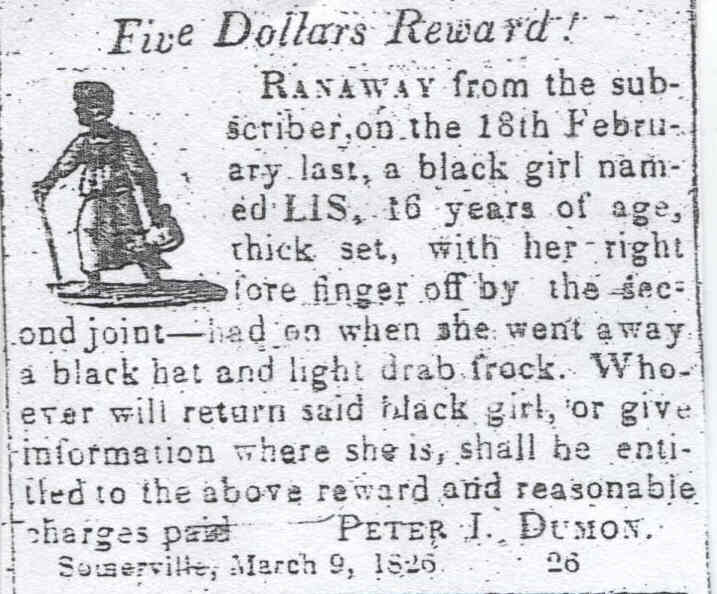

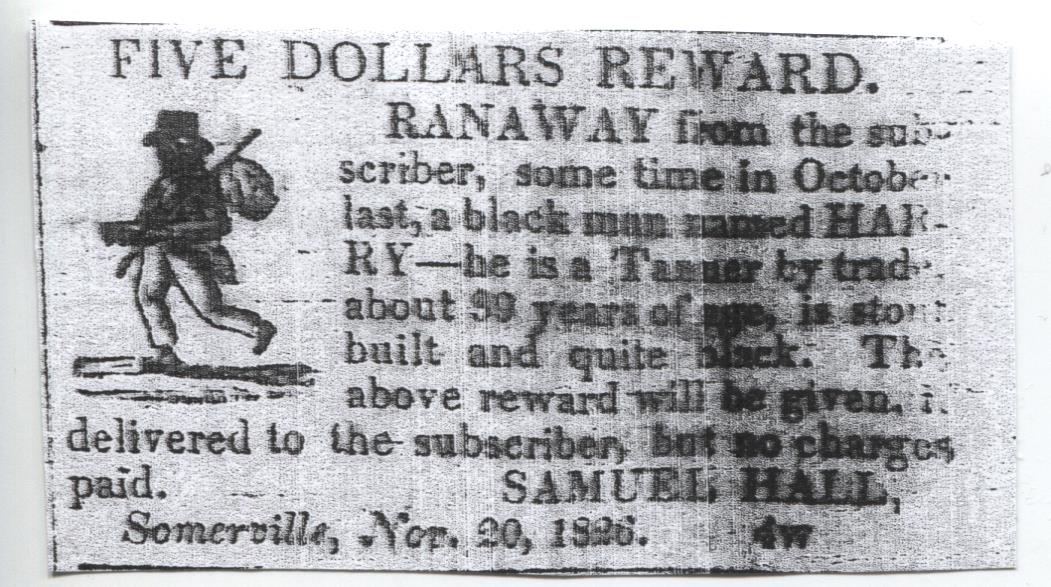

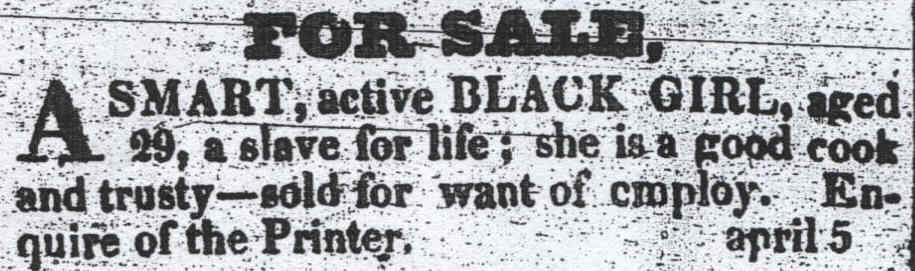

Are Ads from the local newspaper

The Somerset Messenger

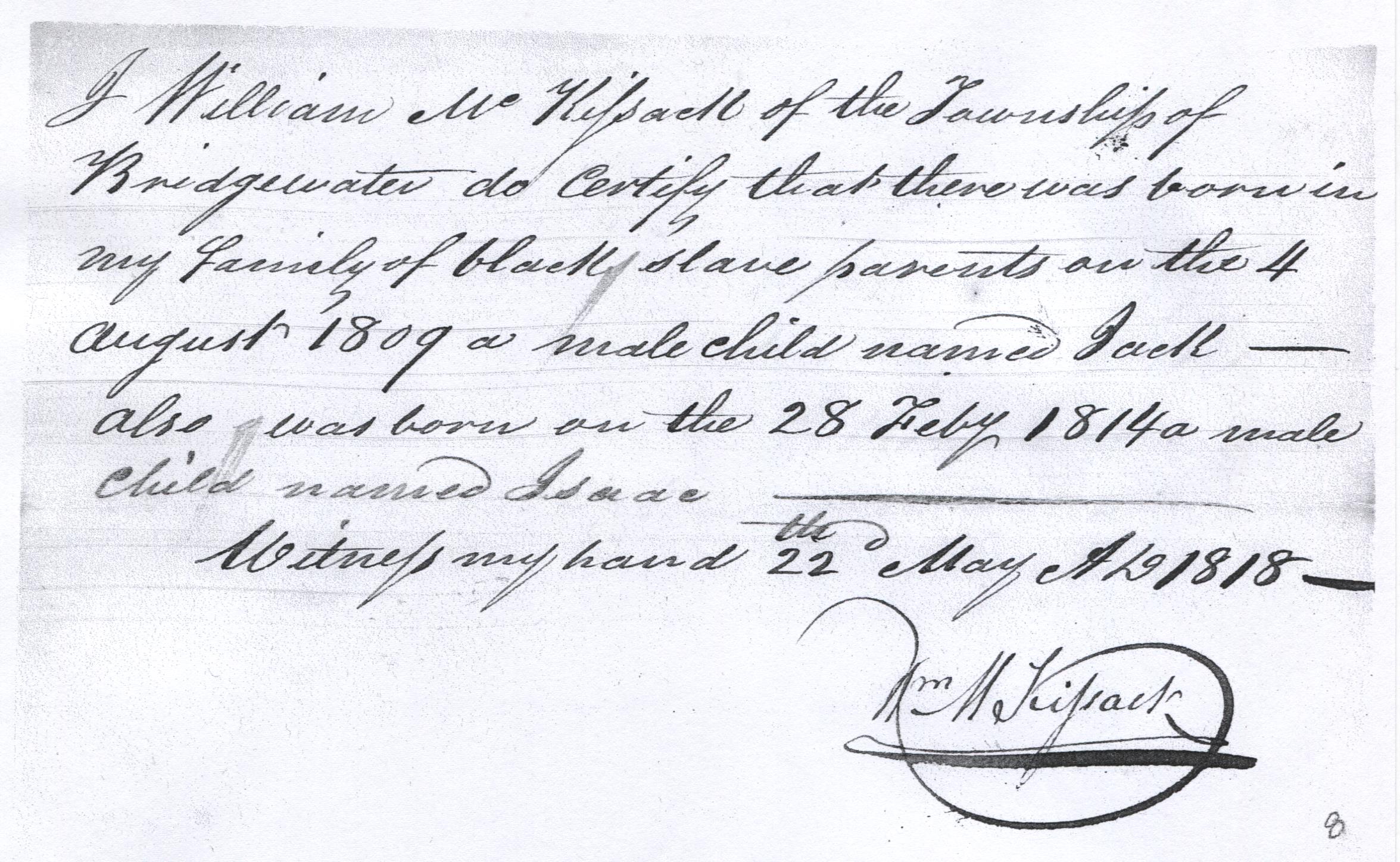

The New Jersey legislature in an effort to appease both groups - the rich/powerful and the common folks - passed a compromise law for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery. The new law stated that any slaves would still be slaves for life, but any of their children born after 1804 would be freed after serving their owner for a period of time. This period was 21 years for a woman and 25 years for a man. These children were labeled “slaves for a term.” This law took the pressure off the lawmakers, but at the time did not free a single slave. The common folks were not entirely pleased with the law, but it was similar to what surrounding states had passed a decade before so it would have to do. Many who strongly believed in the abolition of slavery fought on for the complete freedom of all slaves, but without the internet to communicate and with the people in New Jersey so scattered about , in frustration they abandoned their efforts after a few years.

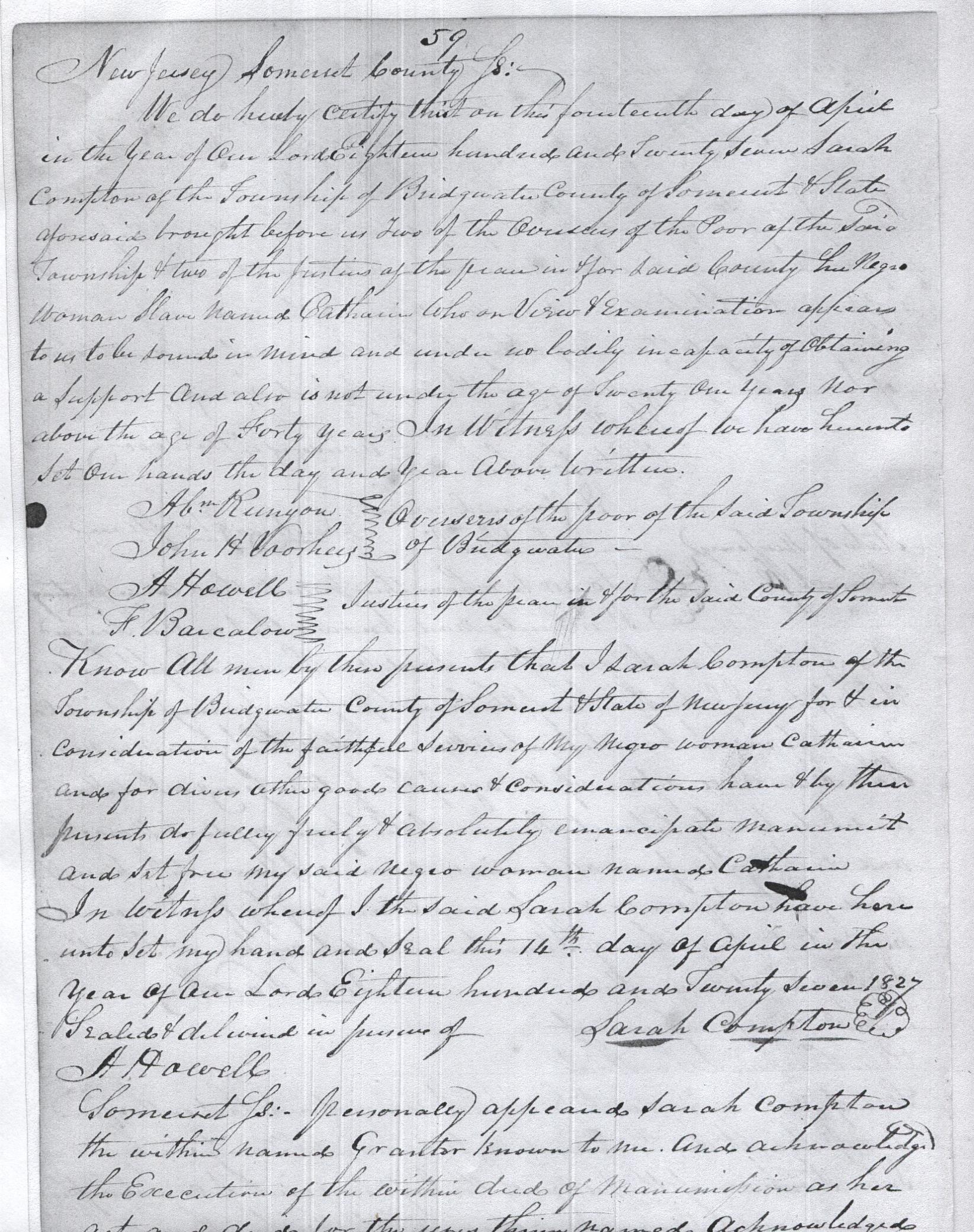

Click to see full view and wording typed out

|

|

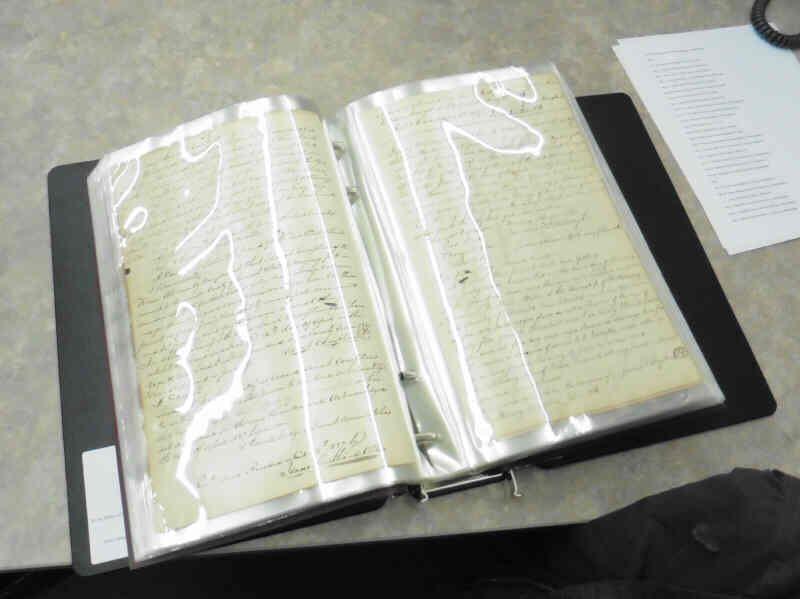

They take me to the records. The documents are in several binders with each page in thick plastic, well protected indeed. There are 352 records of owners freeing their slaves. And 736 birth records for slaves being born as “slave for a term”. The records are hand written, hard to read, but with patience one can make out the wording. The birth records are short and simple stating the slave owner’s name, the slave parent’s name, the child’s name and the date of birth. The documents granting Freedom are a full legal size page. Their purpose was to show that the owner was freeing a slave of sound mind who could function on his own. While this may seem to be a humanitarian effort for the slave’s benefit, it was as much to make sure that the newly freed slave would not become a burden on society.

And then there is Michael Van Veghten whose family’s home in Bridgewater today serves as the headquarters of the Somerset County Historical Society. He was very busy with slaves as 4 birth records and 3 freedom records bear his name.

Then there is the onetime U.S. Senator Richard Stockton Jr. (son of the signer of the Declaration of Independence) who freed his slave Thomas in 1823.

The records show nine slave owners were “Reverends”. One of the Reverends is Bernard’s Robert Finley who established a controversial movement that was designed to ship free blacks back to Africa.

a slave in Bridgewater her freedom

Click to see full view and wording typed out

| Click to see list of Slave Records sorted by "Owner's Name" |

Click to see list of Slave Records sorted by "Town" |

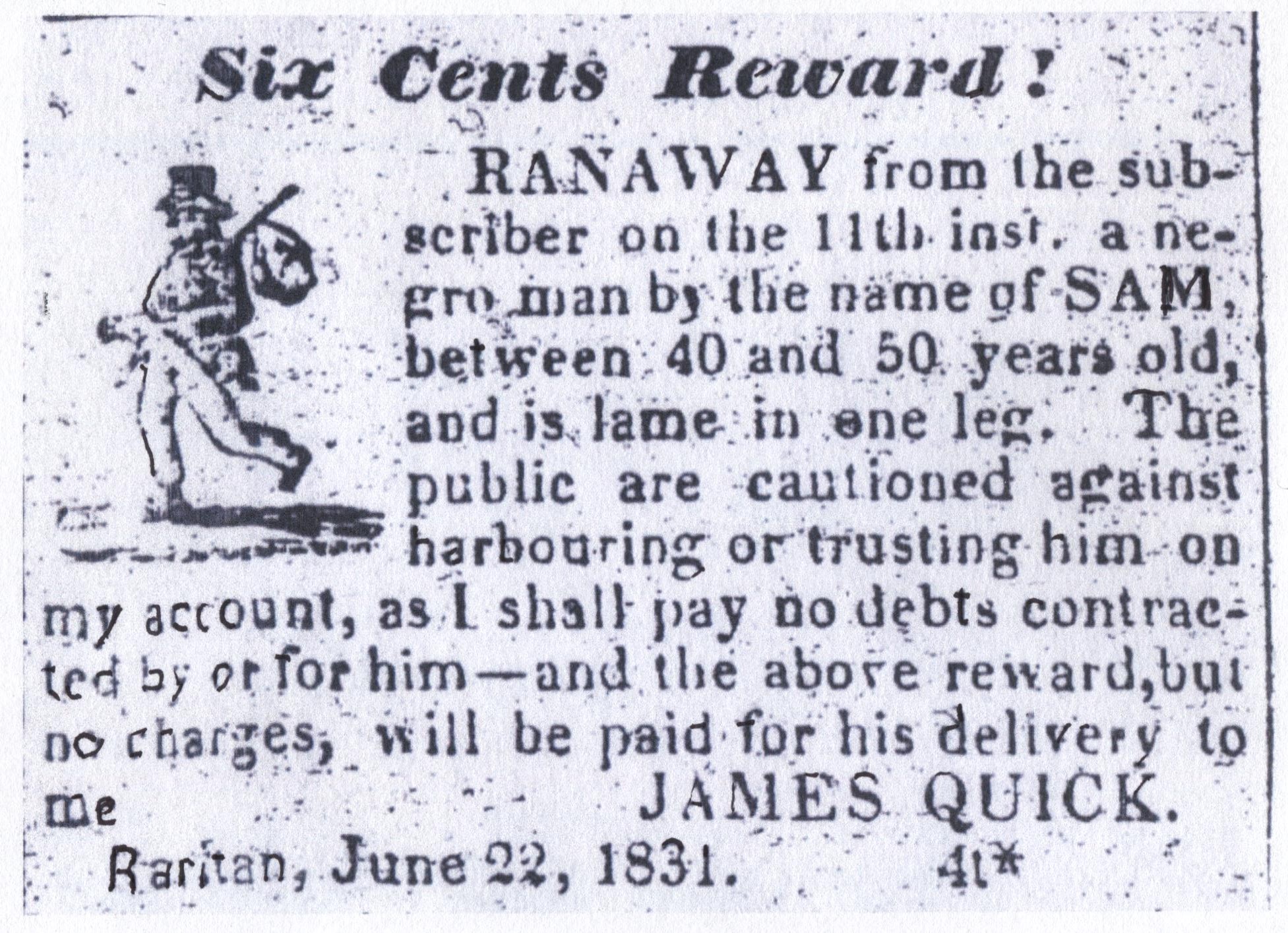

Seeing the towns in these ads say Somerville and Raritan sends chills down my spine. One of the ads for a runaway (summarized) reads: Six Cents Reward – RANAWAY a Negro man by the name of SAM, between 40 and 50 years old, and is lame in one leg. The public are cautioned against harboring him on my account. The above award will be paid for his delivery to me.

James Quick, Raritan, June 22nd, 1831.

FOR SALE – A smart, active, BLACK GIRL, aged 29, a slave for life; she is a good cook and trusty.

So the above is what this author learned about local slavery. Those that read my monthly articles know that I always write a “feel good” story. Things like the heroics of a local soldier or that championship team that took the state title against all odds. But this month there is no “feel good” to my article, only a story of a dark chapter in our history – but a chapter that should be read.